Debuting just a few months after the launch of IBM's PC/AT, the EGA standard allowed users to display an expanded palette of 16 colours (from a total of 64), surpassing the then-popular CGA format, which was limited to a maximum of four (at a resolution of 320 x 200). Because of this, it inevitably became the display standard of choice for many PC owners and paved the way for a new generation of colourful and detailed games from developers like Sierra On-Line, Strategic Simulations, and Lucasfilm Games. While EGA's time on top was admittedly rather brief (it was eventually supplanted by VGA in 1987), there are still many out there who love the EGA aesthetic today and hold it in high regard. Among these is a small and passionate community of indie game developers who have taken it upon themselves to make their own EGA-style adventure games.

GameParadise recently reached out to a few of these developers to find out more about their work and to discover if there's anything more to their appreciation than just simple nostalgia.

The Crimson Diamond - Julia Minamata

When it comes to the topic of EGA games, you'd probably struggle to find someone as passionate about the subject as Julia Minamata.

Minamata is the developer of The Crimson Diamond — a new mystery adventure game that is due out on August 15th — and is regularly boosting the work of other EGA developers on platforms like Twitter and Twitch. As she tells us, she first encountered the EGA colour palette as a kid, growing up playing classic graphic adventure games like The Colonel's Bequest, Quest For Glory 1+2, and The Secret of Monkey Island, and it quickly became her "soft spot for nostalgia". But it wasn't until she found herself struggling while working as a freelance illustrator, that she considered the prospect of making her own. This is when she discovered the free tool Adventure Game Studio.

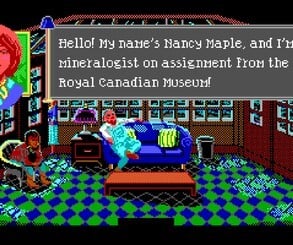

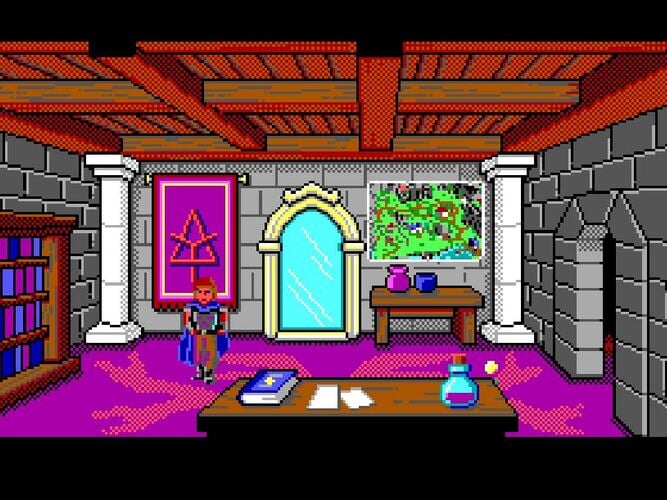

Image: Julia Minamata

Image: Julia MinamataAs she tells us, "I realized, 'Oh, these tools have become so much more approachable than before.' And I started to have these ideas of pixel art and the kind of pixel art I liked, and what I wanted to see. And for me, my instant thought was to try EGA screens. And so, I started experimenting."

As she recalls, she started putting together some art assets and room designs in Photoshop, using old EGA screenshots for reference, before teaching herself Adventure Game Studio's main scripting language and establishing a pipeline for animation. After months of work, she was eventually left with the foundations of a pixel-art house and began thinking about an engaging mystery to populate its interiors.

Images: Julia Minamata

"I like taking visual references and researching them," she explains. "What kind of furniture is going to be in this house? What era is this house going to be? And all of the rest of those things. So that led me to start to think about a game story idea where it's set in a particular era and one of my favourite time periods is sort of that golden age of mystery time you see in Agatha Christie novels. So that's where it all started. I started thinking about who lives here and why and all of the rest of it."

The story of The Crimson Diamond focuses on the exploits of an amateur geologist turned reluctant detective named Nancy Maple, as she arrives in the ghost town of Crimson, Ontario to investigate the discovery of a mysterious diamond. It plays out like a classic EGA-style text-parser adventure, with Maple having to interview the other residents living in the town, eavesdrop on private conversations, and use items to access clues and conversations to advance through the plot. Minamata's ultimate goal with the project was to take what she loved about the Sierra adventure games of old (particularly The Colonel's Bequest) and meld it with a more approachable design philosophy that doesn't unnecessarily punish the player with illogical puzzles and ridiculous mazes.

Images: Julia Minamata

When we ask Minamata what appeals to her so much about the EGA era of games, she has a long list of reasons. Nostalgia is obviously a key factor, but she also told us about how she preferred the clarity of EGA visuals over VGA, enjoyed its bright and often unnatural colour palette, and appreciated the fact that the artwork leaves room for interpretation.

As she explains, "I've always felt this way about just about any form of art form, but I want to see an enhanced or interpreted version of reality. I don't want to see reality. Even nowadays with these games that look incredible – these incredible 3D games that look very realistic – I have no interest in playing them. I'm more interested in how an artist sees the world. And what EGA does is, yes, it's an abstraction. Because it was designed for expediency's sake. It was this idea of you have one yellow; that's it. So the yellow has to represent corn and bananas and gold and straw and everything under the sun.

She adds, "The closest thing that I can think of in real life that represents that is Lego – the way Lego used to be before they expanded the palette. With Lego blocks and bricks and the rest of it, there was this idea that the context of that colour matters. So if you have a yellow brick in a barn, it's a haybale. If you have a yellow brick in a bank, it's a gold bullion or something. That reinterpretation of the same element is something that I really enjoy. I'm always a huge fan of limitations."

Telwynium - Dave Lloyd (Powerhoof)

Similar to Minamata, the creator of Telwynium, Dave Lloyd, has fond memories of playing EGA titles as a kid. As he tells us, some of the earliest games that he remembers playing were Conquests of Camelot: The Search For The Grail, and the first two entries in the Quest for Glory series. For him, the limited colour palette was one of the main features he found appealing about these types of games, as it enabled him to interpret the art in a way that more graphically advanced point 'n clicks wouldn't typically allow and encouraged artists to use more extreme colour choices to produce more striking imagery.

"There was just something that was so special about that," Lloyd explains. "It just sort of made it so that my brain fills in the gaps a bit more and it often became more real than when it's a beautifully painted picture.

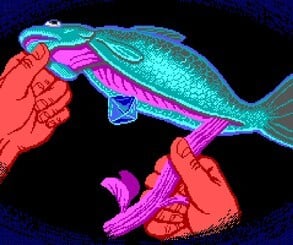

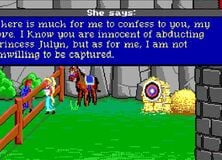

Images: Powerhoof

"I [also] think that because EGA is so limiting, it kind of forces the artist to work with really high contrast. So there's a lot of really deep shadows and bright colours, whereas when you've got any number of colours you want, the art tends to be lower contrast. You have a lot more gradients, and you tend to use not as much colour. So it's kind of like having the colours feel a little bit off in a funky way, but it makes the end result really evocative and interesting to look at."

Lloyd has worked on many adventure games in the past featuring different styles of pixel art, including Intergalactic Wizard Force, Peridium, and The Inanimate Mr. Coatrack — and he is also currently in the process of developing another named The Drifter. However, as he notes, the majority of these titles haven't typically leaned too hard on nostalgia or been explicit references to the games he liked growing up. Telwynium is, therefore, a bit of an outlier.

The four-part adventure game (the final entry, Book Four, is currently in the works) was initially conceived during Adventure Jam 2021 and came about due to Lloyd's desire to make something that brought all of his teenage influences together in one place. This included his love of EGA games like Quest for Glory and his appreciation of books like The Wheel of Time and The Lord of the Rings. According to Lloyd, each of these games is being made using a mixture of the image-editing software Aseprite (with a dithering plugin called EGAify) and Lloyd's own 2D adventure game toolkit PowerQuest (for Unity).

"I'd done a few of adventure games and they'd done quite well and I'd been trying to make more modern style things," he tells us. "For Adventure Jam 2021, I wasn't really sure what I wanted to do, so I thought I would just try and do something super nostalgic and lean really heavily on the nostalgia. So it was kind of going for the art style that was the most nostalgic for me, and also the themes that were the most nostalgic, which was really cheesy fantasy as well as Tolkien/Lord of the Rings kind of stuff, and Robert Jordan's books. That was the stuff I was reading when I was a teenager and getting into that sort of thing. So that was kind of the start of Telwynium."

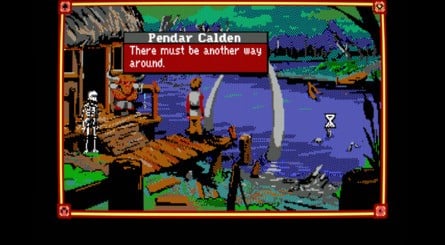

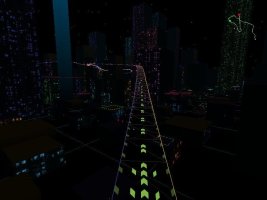

Images: Powerhoof

As he explains, "The initial idea was what if you have a Wheel of Time book or say The Hobbit, but the first night Bilbo is away from the Shire Gandalf is murdered? So, how does that change things? So it starts out very similar to things like Wheel of Time but then tries to twist it and turn it on its head pretty quickly."

Telwynium sees players step into the role of a young hero named Pendar, who has fled their home along with a ragtag group after a devastating attack from the Shadowfell — a group of monstrous demonic beings. After the leader of the fellowship — the magic-wielding Aldor — is killed in the night and your friends are taken, it falls to you to locate the culprits and rescue your missing allies. Throughout the four books, there are various twists and turns in the story, with the end of the first entry seeing Pendar become a necromancer capable of raising the dead after retrieving Aldor's staff.

When it comes to the design of these games, Lloyd decided to go for a point-and-click interface over a text parser, letting you switch between options for looking, walking, and interacting with something. Players have a visible inventory on screen and will have to use the items they collect to solve a bunch of puzzles in the environment. According to Lloyd, there are no unwinnable situations, but he did design the game with an old-school mentality that requires players to be a bit more patient and take the time to scan the environment carefully.

"For Telwynium, because it's my fun, sort of personal side project thing, I've been a bit more relaxed about just having the puzzles be what they are," he explains. "I'm still trying to signpost things really nicely and avoid having any Walking Dead situations where you forgot something right at the start and now you can't finish the game or anything like that, but it is a game where you have to look at everything. That is not a modern sort of thing. Most people don't ever use the Look verb in modern adventure games. So yeah, it is a game where you really have to look around the whole scene with the eye and read the information that it says and see if there's a clue […]. So that's an older style of gameplay that I do like, but it's deliberately a bit clunky and a bit dated".

Betrayed Alliance - Ryan Slattery (Slatt Studio)

While the previous two titles recreate the EGA aesthetic with a modern toolkit, Slatt Studio's Betrayed Alliance is a bonafide DOS game made using the SCI0 engine, which was Sierra's old game engine.

It was originally released in 2013 as a solo project and has recently received a massive overhaul as part of the Kickstarter incentives for its sequel earlier this year. This update features brand-new art from Karl Dupéré-Richer and a true DOS soundtrack from Brandon Blume (who also notably composed the music to The Telwynium).

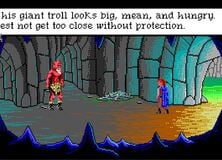

Images: Slatt Studio

It was inspired by its creator Ryan Slattery's experience of playing classic games like King's Quest IV, Space Quest III, and Quest for Glory, and features the common video game trope of rescuing a kidnapped princess. Players assume the role of a young hero who was falsely imprisoned and must set out across a colourful world filled with fantasy creatures and magic to save the missing damsel.

"I just loved the type parser," Slattery says. "I loved the colorfulness of the graphics and all that. I think I originally announced that I was working on this 15 or 16 years ago just on a small little forum of people working on this kind of stuff. Nobody was really working with EGA games. They were working on AGI games, like the double-wide pixels from Space Quest 1 & 2 and all those earlier games. And they were waiting for the next iteration of the studio to make VGA games. So the games that I was working on – or at least the style of the games that I was working on – it seemed very small back then."

As Slattery tells us, the game was originally meant to be much longer, but after he had his first child, he released the original version of Betrayed Alliance online under the title Book One (of three) as it represented one-third of the entire story. At the time, he didn't know whether he would eventually finish the other parts, but after he started seeing other projects spring up online like The Crimson Diamond, he got the confidence to work on the project again, believing that there must still be an audience for EGA-style games. In 2021, he began a Kickstarter for Book Two and included a stretch goal of an enhanced version of Book One.

"I was like, 'Great, that's going to be a lot of work'" he tells us. "So my friend Karl said, 'Well, just tell me what you want me to do and I'll start doing it.' So I sent him the map and he was like, 'I'm going to focus on these screens' and he just did those and then I just worked on the other ones whenever I had time. So he ended up doing about two-thirds of the artwork on the update.

Images: Slatt Studio

"The learning curve was a little bit hard because we're doing actual vector-based artwork, not just I've taken something from Photoshop and I'm going to paste it. It's actually DOS-based stuff. So there was a bit of a learning curve learning the tools. But he picked it up really quickly. He's just a really accomplished, professional artist, so he was able to replicate my style very well while at the same time elevating it and teaching me how to do things better. I'm levelling up my skills watching him."

Similar to The Crimson Diamond, actions in Betrayed Alliance are inputted using a text parser, with players entering a combination of verbs and nouns to direct the character to interact with specific objects. But unlike The Crimson Diamond, Betrayed Alliance also features some basic combat, modelled after Quest For Glory II, where players must use the arrow keys on their computer to swing their sword or block.

Image: Slatt Studio

Image: Slatt Studio"I was definitely inspired most by Quest for Glory," he tells us. "That was kind of like an RPG. But in building the game itself, I kind of shied away from all of the stats-building stuff — like if you need to climb this tree, you'll need a certain amount of a climbing stat. So it feels almost more like a King's Quest or a Space Quest game where it's like yeah, it's kind of your basic puzzles without as much of your stat stuff."

To finish our conversation, we ask Slattery why he thinks more indie developers are starting to make EGA-style games today, and he responds, "I think that 99.98% of it is just the cycles of nostalgia. When the people who are young who are playing it are old enough to create, part of their creation is going to be the things that made them feel great when they were kids. So that's true for me. Even 20 years ago, when I found the program, I was like, 'Oh, I can make that kind of stuff? I'm going to try that.'"

And That's Not All...

Of course, it needs to be said that these three developers aren't the only ones making excellent EGA-style games today. During our research, we also came across Thedeivore's The Perilous Night, Colin P.'s Sesari, and Cosmicvoid's Elsewhere in the Night, thanks to Julia Minamata's recommendations, and we're betting there are a whole lot more that we've missed too.

Once considered obsolete, EGA-style graphics are finally coming back into fashion, thanks to a combination of nostalgia and artistic preference. A whole new generation of developers is revisiting the aesthetic, hoping to replicate the games of their youth and share it with a new generation.

As Dave Lloyd points out, this type of nostalgic reappraisal across generations of artists is nothing new and is actually something that the music producer Brian Eno summed up rather eloquently in his 1996 book "A Year With Swollen Appendices": "Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable, and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit - all of these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided."

While VGA graphics may be the more realistic and painterly of the two formats, there's just something that is still incredibly compelling about the EGA palette and the vibrant and surreal worlds that it brings to life.

What are your thoughts on the recent EGA revival? We'd love to read your thoughts in the comments below!